5 Social Housing Myths Debunked

- arqdiary

- Jun 11, 2025

- 3 min read

The Truth About UK Council Housing

Council housing in the UK carries a heavy burden of stereotypes, and many of them just don’t hold up under scrutiny. From myths about design quality to misconceptions about who lives there, these assumptions have shaped public opinion and policy for decades. It’s time to set the record straight.

Myth 1: Council Housing Is Low Quality

One of the most persistent myths is that council housing is cheaply built and poorly designed. In reality, many council estates were the product of visionary architects committed to quality, community, and longevity. Take Dawson’s Heights in London, designed by Kate Macintosh when she was just 26 years old. Every home features dual-aspect windows and private balconies with sweeping views of the city, carefully planned to maximise light, ventilation, and dignity. This wasn’t cookie-cutter housing; it was architecture with heart.

Example: Dawson’s Heights, East Dulwich

Designed by Kate Macintosh in 1964–72, this iconic development features carefully planned dual-aspect flats, private outdoor space, and a striking silhouette that integrates with the landscape. Far from low quality, it exemplifies thoughtful, dignified architecture.

Myth 2: It’s All Concrete and Grey

While brutalism and concrete often come to mind when people think of council housing, the reality is much richer. Council estates showcase a wide range of architectural styles—from modernist innovations to colourful post-war designs that embraced texture, pattern, and greenery. Estates like Golden Lane, Alexandra Road, and Park Hill reflect an attention to detail and aesthetic variety that challenges the idea of bland, grey blocks.

Example: Golden Lane Estate, Barbican

Completed in the late 1950s by Chamberlin, Powell and Bon, Golden Lane is a vivid contrast to the "grey" stereotype. With brightly coloured panels, communal gardens, and a mix of low- and mid-rise buildings, it reflects a playful, humanistic approach to design.

Myth 3: High-Rise Means Poor Design

High-rise living often gets a bad rap, but it doesn’t have to mean sacrificing quality or community. Thoughtfully designed towers can offer better access to daylight, ventilation, and views than many private developments. Dawson’s Heights again proves this point, with its stepped terraces ensuring every flat is dual aspect. Good design can humanise height, turning it from an isolating monolith into a place that uplifts residents.

Example: Trellick Tower, North Kensington

Ernő Goldfinger’s 1972 brutalist high-rise is divisive in aesthetics but undeniably rich in design logic—every flat has a balcony, and communal areas are integrated throughout. Despite years of underinvestment, it remains a bold vision of vertical living.

Myth 4: Council Housing Is Only for the Poor

Historically, council housing aimed to create mixed communities across income levels, providing affordable, quality homes for a broad demographic. Today, rising housing costs and policy shifts have altered this balance, sometimes unfairly stigmatising residents. It’s important to remember that council housing was—and should be—about accessibility and opportunity for everyone.

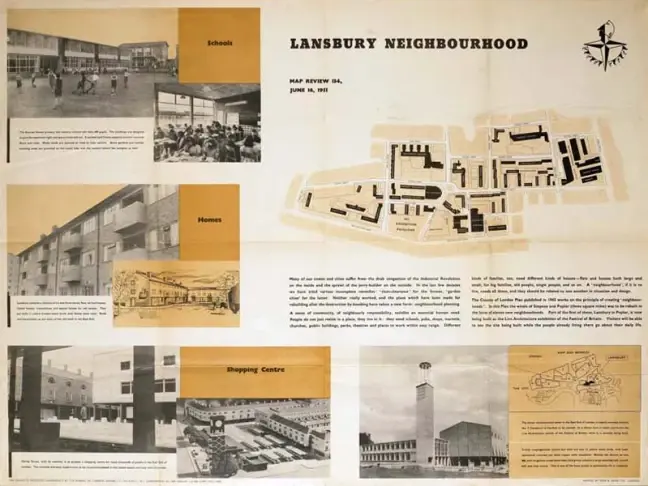

Example: Lansbury Estate, Poplar

Built as part of the 1951 Festival of Britain, the Lansbury Estate was a model of a mixed-income, well-planned neighbourhood. With schools, churches, and markets integrated into its layout, it reflects the ambition of council housing as an inclusive, civic infrastructure.

Myth 5: Council Housing Is a Failed Experiment

The real failure isn’t in the architecture—it’s in the chronic underfunding and lack of maintenance many estates have suffered over the years. Properly cared-for council estates can thrive as vibrant communities with strong social networks. The design foundations were often solid; it’s the investment and care over time that need to catch up.

Example: Boundary Estate, Shoreditch

Completed in 1900, this is one of the earliest examples of council housing in the UK. It’s still lived in today and is considered a success in community building and urban regeneration. Its longevity and adaptability show that when maintained, council estates can thrive for generations.

Why It Matters

Debunking these myths isn’t just an academic exercise—it has real implications for how we talk about housing policy and community development. When we recognise the value and potential of council housing, we open the door to better investment, better design, and more inclusive, sustainable cities.

Council housing deserves a fresh look—one that honours its history, celebrates its successes, and challenges us to build better futures for all.

Comments